•Rays

Stingrays, electric torpedo rays, skates, and more rays!

Rays and sharks are a cartilaginous group of fishes, which together form the Elasmobranch suborder. These are characterized by having 5 to 7 gill openings that are lateral in sharks and ventral in rays, slow growth, late age at maturity, low fecundity, and an extended lifespan. Unfortunately, many ray species are accidentally caught in fishing nets. As stingrays are of little commercial value they are discarded at sea, thus little is known about their population sizes and trends.

In Menorca divers are likely to see 6 species of ray;

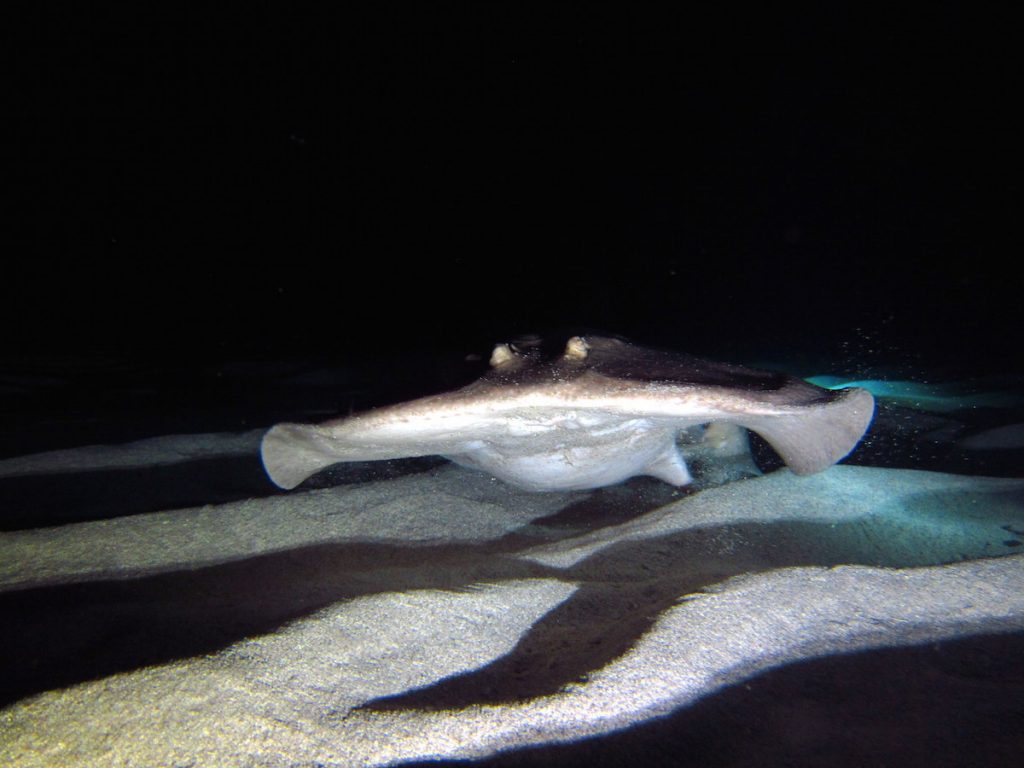

Marbled torpedo rays (Torpedo marmorata). It was Aristotle (384-322 BC) who first dissected torpedo rays, and who described the electric shock they produce, by poking electric rays with a metal rod. The powerful jolt produced when touched was used to treat people suffering from gout, headaches, or epilepsy. A preference for water temperatures below 20⁰ C may explain why these rays are more often seen by divers in winter than in summer. most adult rays are a darker colour on their dorsal side, and lighter on their underside. This is called “countershading”; when seen from above, the animal blends in with the dark ocean depths or seabed. The underside blends in with the lighter surface of the sea when seen from below. This makes rays harder for predators or prey to spot.

Common eagle rays (Myliobatis aquila) and undulate rays (Raja undulata), not pictured, are less commonly encountered

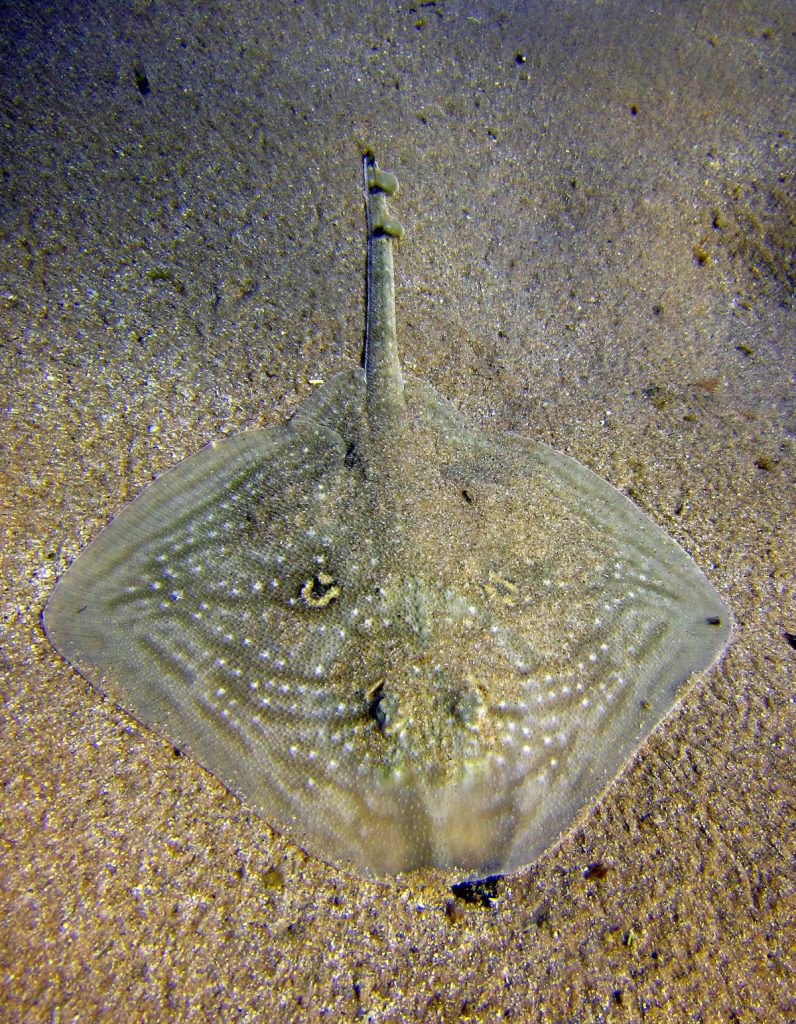

Rough skates (Raja radula). Rough skates are endemic to the Mediterranean and have been classified as Endangered on the IUCN Redlist, which means they’re at high risk of becoming extinct in the wild. Eyespots on the pectoral fins may afford protection by deceiving predators into attacking the fin rather than the more vulnerable head. Eyespots can also dissuade potential predators by making the ray appear to be a larger animal, momentarily stunning predators when the ray unburies itself to flee.

The huge roughtail stingrays (Dasyatis centroura), which we only see on rare special occasions, can get to 4m long and weigh up to 300 kilos! A very lucky group of divers in the picture below give us an idea of scale.

By and large the most abundant ray sighted by divers in summer is the common stingray (Dasyatis pastinaca). Stingrays feed and live on the seabed. Electro sensory organs on their snouts and strong senses of touch and smell allow rays to root out prey. Their purely carnivorous diet is made up of shrimps and bivalves, as well as small crabs and bottom dwelling fishes. Many rays are nocturnal, making extensive forays to feed at night, and remaining largely inactive during the day.

Because it takes years for rays to become sexually mature, and because the number of offspring produced is then small, the majority of Mediterranean ray species are overfished and endangered (The Conservation Status of Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras in the Mediterranean Sea, IUCN Report). Solutions to their plight involve investing in technologies that reduce bycatch (such as exclusion devices, and different net designs), ensuring the complete eradication of driftnets, (which although illegal, are still widespread in the Mediterranean), and the establishment of marine protected areas in places that we know are important as nursery and feeding grounds (www.fao.org). Some law enforcement wouldn’t go amiss either.

Stingray courtship and mating

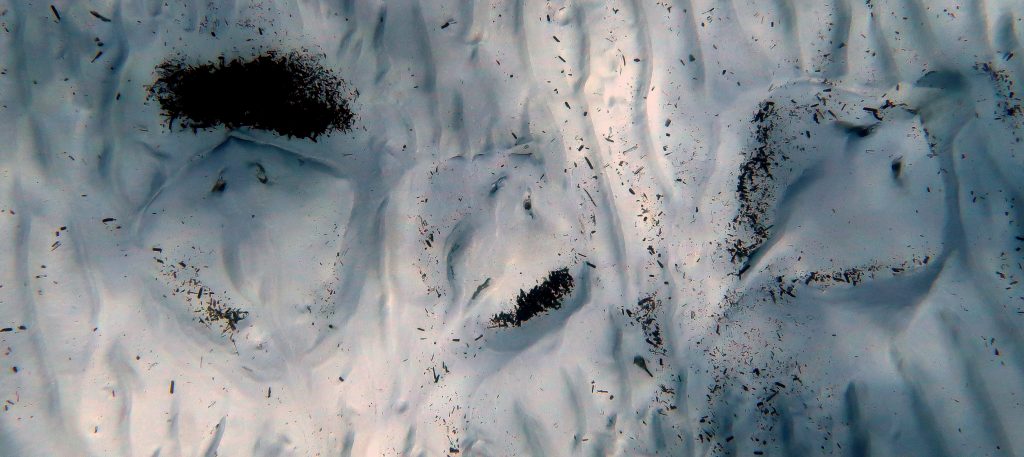

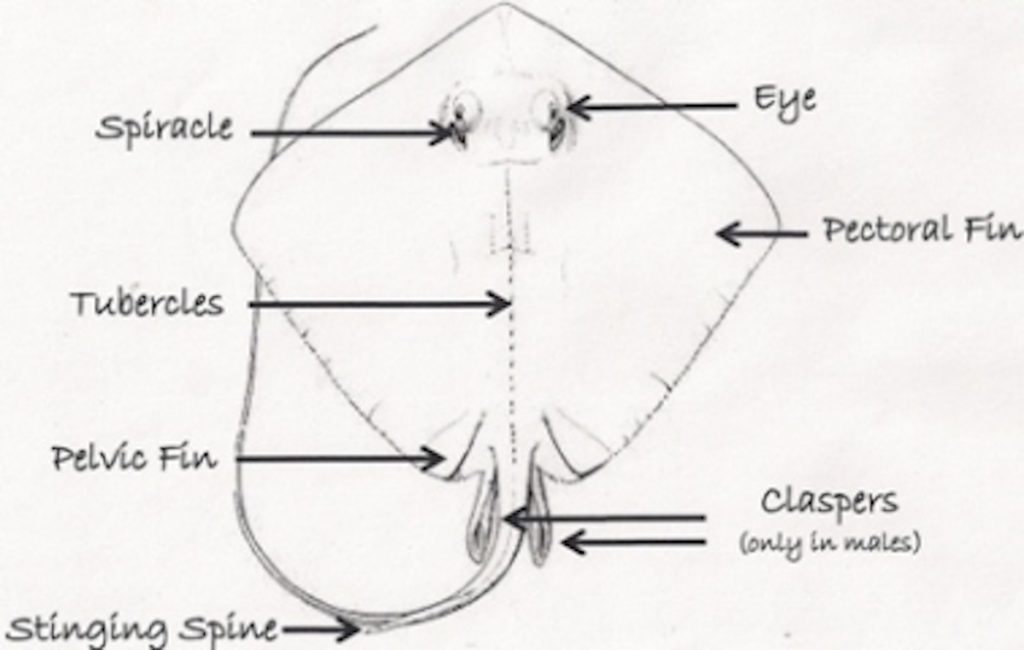

For most of the year stingrays are solitary, inhabit deeper waters, and are rarely seen by divers. However, during the mating season, from April to July common stingrays aggregate on inshore bays to mate, providing a unique opportunity to see their reproductive behaviour in the wild. Pregnant females are distinguished by their enlarged abdomens and backs. Swollen and sluggish, they also prefer to rest in seagrass beds rather than on sand. 4-7 pups are produced after a gestation of around 4 months. Ray pups are fed milk in the womb via special tubes and born as live young. Copulating and parturition in the wild haven’t been recorded for this species, and by July they all disappear, continuing their mysterious life cycle until they return to mate the following spring. During courtship, males often follow females with their acutely sensitive snouts close to the female’s cloacae, in search of a chemical signal that the receptive females emit. In some ray species, electro sensory stimuli emitted by buried females help males to detect them. This may be occurring when “grouping” is observed; groups consist of large females resting or buried in the sand, and numerous smaller males surrounding her, with their snouts orientated towards her.

The picture below was taken by a snorkeller (me!); disturbance to the rays is clearly reduced as opposed to SCUBA diving, due to the increased distance, and grouping activity is much easilier detected from the higher angle. Two large females and a small satellite male just discernable in the middle, facing the rear of the female.

So where is the best place to get our eyes on some stingrays?

For divers, Bluewater Scuba Dive centre in Cala’n Bosch, carries out ray dives on a daily basis. Stingrays abound in the shallow, clear waters of sandy bays, which makes them excellent subjects to view while snorkelling. They are found mostly on the south coast in depths as shallow as 2m. See if you can guess the gender by looking for the male’s claspers, although bear in mind that these only become visible once the ray has reached sexual maturity, which in the Western Mediterranean populations would mean a body width of around 40cm.

Photography

Bottom dwelling rays are often found partially buried in the sediment. Rays breath while buried by using the spiracles behind their eyes, through which they draw in water towards the gills, and then flush it out from the gill openings on their undersides. Unfortunately, photographers often ellicit flight responses to stage their pictures. While this may seem harmless in itself, we are not sure of the disruption caused and so it is best to move slowly and keep within a couple of meters of the rays. If we wait patiently, swimming rays will no doubt cross our screens of their own accord. Flash photography is a stressor to every animal I can think of, ourselves included, and should be avoided.

If you happen to be in Menorca in spring/early summer, chances of finding rays are pretty high, so I encourage you all to grab a mask and go find out for yourselves how very amazing they are.