•Fantastic seagrass, or “dirty unkempt beaches”

Every year come August, my friend’s father used to pack their camper van full of tables and chairs, buckets and spades, food, the dog, and even a portable T.V. They would then drive to Son Saura, literally across the sand dunes, to the far end of the bay where they would spend the next three weeks. That was only 30 years ago. Not quite the same today. The sudden increase in mass tourism has a huge impact on our ecosystems, and that is exactly the point I’d like to make; beaches are living ecosystems, made up of different parts that rely on each other, and that change from year to year. Fundamental to the creation and maintenance of our beaches is the seagrass Posidonia oceanica, also known as Neptune grass, or eel grass. To start with, most of the sand that creates our beaches comes from dead calcified animals that lived on their blades. Every winter the grass sheds its old leaves. Over 80% of dead leaves are transported off the meadows in autumn by waves and currents, and lots of these then ends up on our beaches. The leaves help protect the beach from storms by making the water more viscous near the shore, which reduces onshore wave action. They further protect the beach by accumulating on the sand and forming a physical barrier that stops wind and waves from taking the sand back out to sea. This same barrier prevents water from reaching the dunes at the back of the beach, where the high salt levels would kill the plants. When they decompose, the leaves supply nutrients to both the organisms living within the sand and back in the dunes. Some of the leaves are carried out to deeper waters where they, (plus poop from the organisms housed within the meadow), provide carbon and fertiliser to offshore sediments.

In the water seagrass traps sand and sediment, keeping the water nice and clear for us snorkellers, and for travel agents’ marketing photos. As a photosynthesising plant, seagrass produces mountains of oxygen, and acts as a carbon sink, regulating the chemical properties of the sea. Not bad for one plant! Some years there is naturally more seagrass lying on the beaches, others there is less, and that’s just the way it should be. Beachside businesses urge authorities to ‘clean’ the beaches by using large tractors that sieve the sand free of all particles larger than the mesh size they are rigged with. This removes vast amounts of sand, twigs, and seagrass. These heavy machines, together with thousands of pairs of feet, also compact the sand making it water and oxygen-proof, which is not much use if you’re a cockle or a worm that lives inside of it. Altering the shape of the beach by flattening it all out removes natural windbreaks at the shoreline and near the foot of the dunes. While 30 years ago seagrass was just another part of the beach you either liked or you didn’t, now we seem to think that beaches need to be raked, sieved, and ironed into a flat, barren, and lifeless plateau whose only function should be that of providing humans with a place to put our towels down.

The word snorkel comes from the german schnorchel, and has something to do with noses, snoring, and submarine airshafts. Etymology aside, snorkelling is the Mediterranean equivalent of rockpooling, in that if you want to find animals then it’s into the sea you have to go.

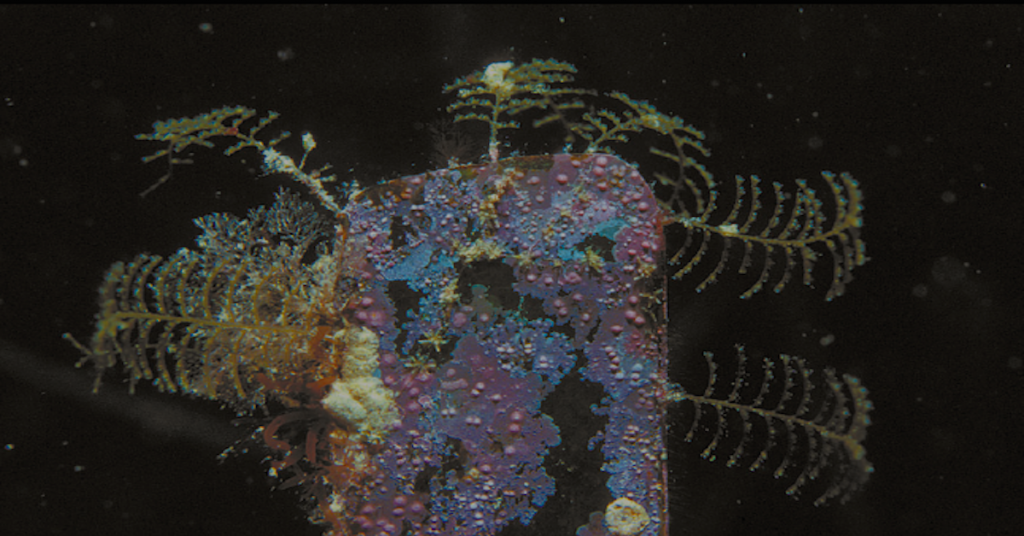

So what exactly is Posidonia?? Originally a land plant, it returned to the sea relatively recently. With extremely slow lateral growth, it photosynthesises, has flowers, seeds, fruits, and a root system, unlike algae or seaweed. Posidonia only lives in good quality waters and so, is what we call a bioindicator of the health of the sea as a whole. It can be found from 5 to 40 m, but most of the life that we see on their leaves (and so excellent for snorkelling) occurs in shallower located plants. The deeper dwelling Posidonia has more species living near its root systems, such as worms, sponges and crabs.

In terms of fish life, seagrass meadows are extremely important as nurseries, in which young fish settle, feed, and hide from larger predators. In summertime you can often see baby barracuda (Sphyraena spp.) in small groups, individuals no more than a finger long. They are unmistakable due to their fusiform shape and pointy noses. Salema, or cow bream (Sarpa salpa) are herbivorous, deep-bodied with yellow stripes, and graze in seagrass, leaving clearly visible nibble marks along the grass blades. Apparently, they retrace the same route every day. Don’t be surprised to find faecal pellets falling through the water column in a trail as they graze their way through the meadow. Salema are of the few bream in the Mediterranean to become herbivorous as adults; most of our bream begin life as omnivores then become carnivores and shift to eating invertebrates.

Young green wrasse and pipefish also live in the meadow, the latter, often hanging motionless near the top of the canopy, can be very hard to spot. Pipefish are related to seahorses and similarly, it’s the males that have pouches to carry the offspring.

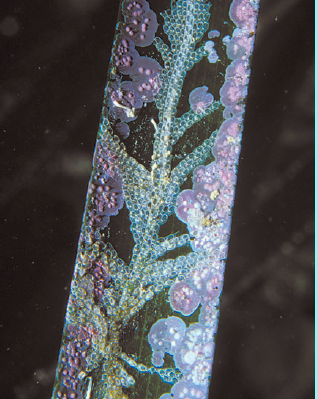

Today I was fascinated to observe the zonation of communities inhabiting the leaves. Due to the leaves growing so quickly, (up to a metre a year) and lasting on average 300 days, species must be quick to find a suitable patch on which to settle, grow and reproduce, before other competitors do instead. Hydrozans (Sertularia perpusilla) competing for space follow the new leaf growth and grow downwards. Calcareous red algae (Fosliella sp.) grow on the outer margins of the blade, whilst bryozoans (Electra posidoniae) branch up the middle wherever they can find space. Near the tip of the leaf, we find fleshy red algae and brown algae (Dictyota spp.) that need lots of light for photosynthesis.

Calcified bryozoans may choose to live right on the tip of the leaf, where there is enough water movement for them to catch food from with their tiny tentacles. In spring, fresh new shoots are bright green and squeaky clean, yet as the summer wears on the leaves gradually become colonised by sea squirts, anemones, and calcareous algae and animals, which make the leaves appear almost totally white.

When the leaves die off and break down, the skeletons of some of these organisms become our sandy beaches.

Mooring buoys are all the rage at the minute, but before we get carried away by distressing footage showing the seabed being ripped up, let’s check who made them, as hearsay is that private companies hoping to get rich are behind the making of some of these videos. Although, then again, so what really? While it is common sense to install buoys, these need to be specially designed in order to minimize damage, and one would hope, fairly managed. Boat hire companies should inform customers that it’s now illegal to anchor in seagrass, and that even if we choose a sand patch, we may still end up dragging in to the seagrass.

While anchor damage is a concern in areas where lots of boats gather together, the major threats to seagrass are pollution from untreated waters entering the sea (high nutrient input means that algae may bloom and smother the plants), and increased sedimentation due to harbour dredging and coastal development (which makes light levels so low that the plants can no longer feed themselves through photosynthesis).

Ostensibly, the Anglo-Saxon words for sea were “whale road”, “seal house”, and “fish home”, and with that I think I’ve made my point!

Another 2 pipefish, just ‘cos I can!! Deep-snouted pipefish Syngnathus typhle rondeleti, and a spotted piefish Nerophis maculatus