•Spearfishing; common held beliefs and the drivers behind it

Spearfishing has been practiced for thousands of years; pointed sticks, barbed poles and harpoons are mentioned from ancient Greece to the Bible. Nowadays iron spears are shot from elasticated guns and travel at speeds of 200 km an hour. It is highly likely that you are familiar with the spear fishers’ tell-tale floating orange buoys as they hunt along our coasts, a black camouflaged snorkel just a few metres up front.

Spear fishing is widely held to be a less wasteful form of fishing, with no by-catch, leaving behind no lines or ghost nets, requiring no bait, and with hunters being able to decide exactly which “piece” (they call fish “pieces”) to take. When fish were plentiful I’m sure this romantic notion was true, yet how does spearfishing fit in with what we are now discovering about the state of our seas?

I grew up in Menorca and my friends spearfished, I’d often go out with them on weekends, and some of my best times at sea were spent exploring new drop offs and underwater caves.

Only 20 years ago I remember larger fish around, close in shore, groupers in particular. It’s rare to see anything very big in the Mediterranean now, and even smaller fish like bream flee in terror at the sight of a snorkeler. None of my friends fish anymore.

Across the globe, now depleted reefs were initially fished with spear guns, fishermen systematically taking out one top predator species then moving to the next, until they had to resort to lines and nets to get the smaller remaining fish. Increasingly, thanks to satellite navigation and fish finders, previously inaccessible, remote reefs, are now also being targeted. Thus, there is ample proof of how damaging spear fishing can be.

I have been battling with my position on spearfishing for years, until I came to work in Madagascar; where subsistence fishermen still use spears everyday. My fellow western colleagues were intrigued, and for a brief period were all very interested in joining on a spearfishing trip. They were telling me “it’s fine because it’s very selective”. One day I came across a 20 yr old sitting with his prey before him, a squirrel fish and a young picasso triggerfish, he hadn’t hit it square and there was only about half left. It all made for a combined edible area of about 2 square inches. I recoiled in disgust. He looked up at me and smiled ‘I caught my first fish’. Then I realised that the drivers behind spearfishing are many, yet are similar across the world, no matter your income, culture, nor livelihood. Interestingly, food provision is but a small part of why people fish.

I was surprised to find out that our Malagasy boat captain, even though provided with a good salary and thus having no need to fish for food, still goes out to spear fish most nights after work. This is also true for subsistence fishermen in the Pacific. When questioned they answered that they went because they enjoyed the challenge of the hunt, and being out together with their friends on the water.

Australian recreational fishers explained that parents would far rather their children burnt off their energy out at sea spearfishing, or spending quality time with their friends and family on a fishing trip, than causing trouble on the streets. Therefore, there is a large social component to fishing, such as bonding amongst young men as they jostle to earn respect in their societies by becoming the best hunter… Older adults who also fished competitively in their youth explain how they used to earn their reputation by taking as many fish as possible in the shortest time, taking risks to get the largest pieces, and that there was definitely a large part of machismo to it. Take a look at some Facebook images of hunters flaunting trophies- it’s not like any one fish of any size would do because it’s simply nice to eat, but grounds for a show of masculinity and ego. Again, this may not be such an unnatural thing per se, – if there were plenty of fish left to exploit for that purpose!

Encouragingly, older fishermen did want to guide their youngsters towards a more relaxed and sustainable form of fishing. They also explained that fishing was a platform that introduced them to a means of getting away from modern day stress, and thus afforded huge physical and psychological benefits. one man was allowed to spend the day out with his mates as long as he brought something nice back for his wife for supper! These motivators to spearfish are rooted in basic human nature and very hard to argue against.

No one wants to be told what they can and can’t do, and there is definitely an element of hypocrisy in slating spear fishers then buying a trawled scorpion fish at the market, or ordering a grouper at a restaurant, illegally poached from the Marine Reserve (also known to happen). Nonetheless, I believe we have a choice nowadays to partake in less damaging hobbies, such as underwater photography, snorkeling and freediving.

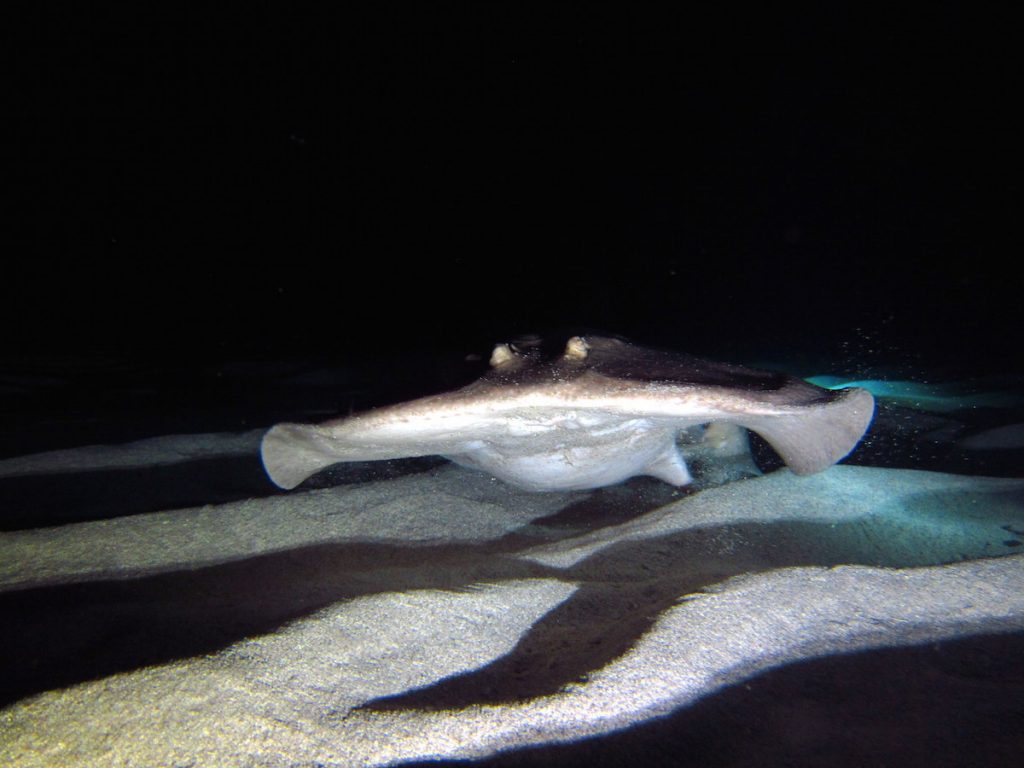

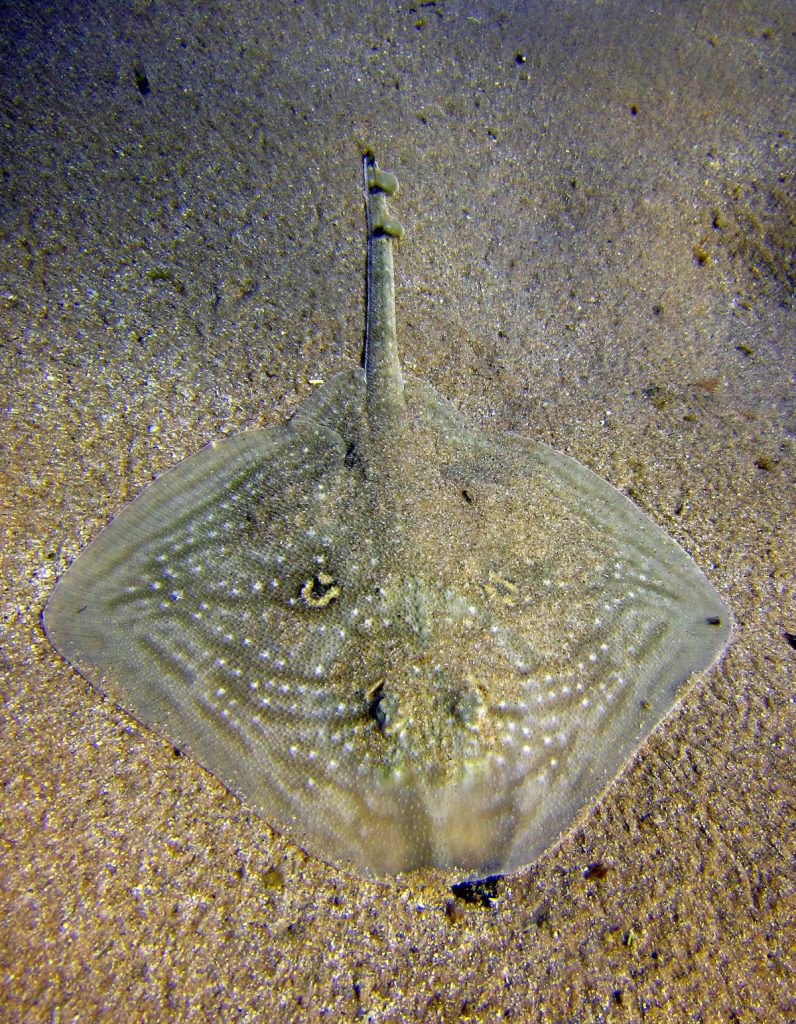

GROUPER BIOLOGY, HOW AND WHY SELECTIVE SPEARFISHING IS SO DAMAGING

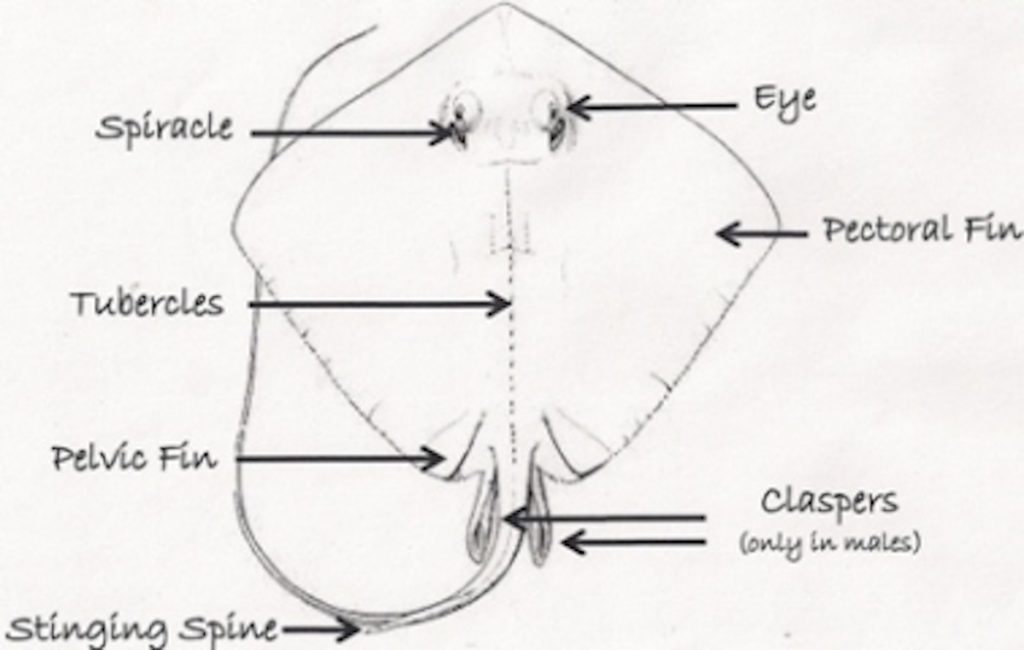

Grouper, or the coveted “Mero”, are often taken by spear fishers and sold to restaurants, for up to 300e apiece. During spearfishing competitions you get points for larger fish, and on the practical side of things it also makes more sense to take out the largest possible fish. In the 80’s it was common to catch up to 15 large grouper a day. Fishers train up to 5 hours a day 5 times a week so it doesn’t take that long to wipe out a large proportion of adult grouper. Research shows an estimated decline of ~88% over 10 years for southern Europe and the Mediterranean prior to 2001; No wonder I remember seeing more of them when I was a young girl. Though it is said that grouper have moved to deeper waters in response to fishing pressure, in any case, good spear fishers can still reach them, even at 50 m. These men (mostly) are well-trained athletes that have paid their annual license fees to FEDAS, and hopefully respect the catch and size limits. So what is the problem?

In a nutshell, larger fish produce more young. Fish eggs float in the plankton for many days, and a lot of these are eaten during this time, thus it is very hard to say quite how many eggs must be laid for any to survive at all. Dusky grouper ( Epinephelus marginatus) are born female, and spend the first 12 years of their life growing big. Once they reach sexual maturity they divert their energy to producing eggs, and after many more years, they may or may not change sex and become males, thus most of the larger older groupers are male. I’ve had a mate argue that he only takes out the older non-reproductive males. This is exactly the problem; first of all, you can’t be sure it’s a male based on size alone, as some of the larger fish are also female and never undergo the sex change. We need the largest females to produce many eggs. We also need some males left to fertilize the eggs. Indeed, research shows that females may not spawn if there are no males (or not enough males) around. The current minimum catch size for grouper is 45 cm from snout to tail, yet we now know that not all females have began reproducing by this size, and that the minimum size should be increased to 50 cm at the very least. Dusky grouper can live to 60 years of age, thus in order to maintain enough males to fertilize eggs, or larger females that produce high amounts of eggs due to their old age, the biggest individuals in the population must be allowed to survive, and scientists recommend only catching grouper between 50 & 80 cm. Size limits need to be constantly reviewed. This research dates from 2010, yet the current (2015) fish sizes from the CAIB still set a minimum size of 45 cm and no upper limit. Even the most respectful well-meaning fisherman can be misled by the continued lack of information and regulations.

In order for them to be effective, new fishing reserves need to ban all forms of fishing, recreational or otherwise, and we need to understand that that should temporarily be the end of the story! Until stocks have a chance to recover, and to be properly managed, we all have to take responsibility for our choices. Spear fishers feel that they are often, ironically, an easy target for environmentalists, as recreational spear fishing is not allowed in marine reserves, whereas line fishing from shore and boats usually is. We shouldn’t discriminate between the two as, in order to glean as much local knowledge as possible, we need all types of fishermen to unite with scientists. All fishing is damaging when the seas are so depleted and humans are so numerous; whether it’s with a rod, a harpoon, or a net in a rockpool, the cumulative impact is huge and relentless. Investment in research, community education, and sharing of knowledge between fishers and scientists is required to ensure the future of our seas. Well, all that and a huge kick up the bot to policy makers that prioritise short term investment over long term sustainability. As Dr Rainer Froese says in his podcast for Blue Marine Foundation , you can’t take credit on loan from the sea today and give it back tomorrow, it just doesn’t work like that.